The thoughts of Ben Horowitz, co-founder and partner at Andreessen Horowitz, on the most effective ways to create systems of behaviors that are followed by most employees, most of the time and in the most situations

Central Ideas:

1 -Culture is not a magic set of rules that makes everyone behave as you would like them to. It is a system of behaviors that you expect most people to adopt most of the time, in most situations.

2 – No culture can flourish without the leader’s participation. No matter how well defined, well programmed the elements that constitute it, an inconsistent way of behaving by the leader undermines all these efforts.

Modern companies tend to focus on objective data such as goals, missions, and quarterly balance sheets. They rarely think about why employees show up to work every day. Which is more valuable? The money or the personal growth? Culture cannot be unrelated to these questions.

4 – To understand the culture, the best is not to know what managers say, but to observe the behavior of new employees. What are the behaviors that, in their perception, will help them integrate, survive and thrive in that environment?

5 – In the company’s environment, focus on the problems, not the people. If you identify a problem, look for the main reason that caused it. Most likely you will find that the problem was communication, or misunderstood priorities, not a mistake by a negligent or short-sighted employee.

About the author:

Ben Horowitz is co-founder and partner of Andreessen Horowitz, a venture investment firm that invests in entrepreneurs. He is also the author of the best-selling The Hard Side of Difficult Situations. Horowitz holds a master’s degree in computer science from UCLA and a bachelor’s degree in computer science from Columbia University.

Introduction

When I started LoudCloud, I sought advice from CEOs and industry leaders. They all advised me, “Pay attention to company culture. Culture is the most important thing.” However, when I asked these leaders, “What is culture, exactly? How can I create my company culture?” they all gave very vague answers. Over the next eighteen years, I kept looking for an answer to that question. Would culture be the ability to bring your dog to work or practice yoga in the break room? No, those things are perks. Would it be the company’s values? No, values are aspirations. Would it be the CEO’s personality and priorities? No, they help shape the culture, but they are far from being the culture itself.

On the other side of the continent, in California, a group of engineers created a series of cultural innovations that ended up changing the way virtually every company operates. In the 1960s, Bob Noyce, co-inventor of the integrated circuit or microchip, ran Fairchild Semiconductor, a unit of Fairchild Camera and Instrument Corporation. Fairchild Camera, based in New York, did business in the East Coast style, which was the way big companies were conducted throughout the United States. Sherman Fairchild, the owner of Fairchild, lived in a marble and glass mansion in Manhattan.

Bob Noyce did not believe that such things made sense because it was his engineers – the small free farmers – who made the business work. So Fairchild Semiconductors adopted a different way of doing things. Noyce did not hire professional managers. He stated, “Today, the main quality of leadership is coaching, personal guidance, not direction. You have to get the obstacles out of the way to let people do what they know how to do.” So a new culture was created, where everyone was their own boss: everyone was responsible, and Noyce was only there to help. If a researcher had an idea, he could study and develop it over the course of a year before anyone started asking him about the results.

At Intel, Noyce took his egalitarian ideas to a new level. Everyone worked in a single room, separated only by partitions. Noyce himself sat at a second-hand metal desk. Lunch was sandwiches and soda. There were no lawyers or vice presidents in the company.

Culture is not a magical set of rules that makes everyone behave as you would like them to. It is a system of behaviors that you expect most people to adopt most of the time in most situations. No large organization achieves one hundred percent observance of all its values, not by a long shot, but some do much better than others. The goal here is that we become better, not perfect.

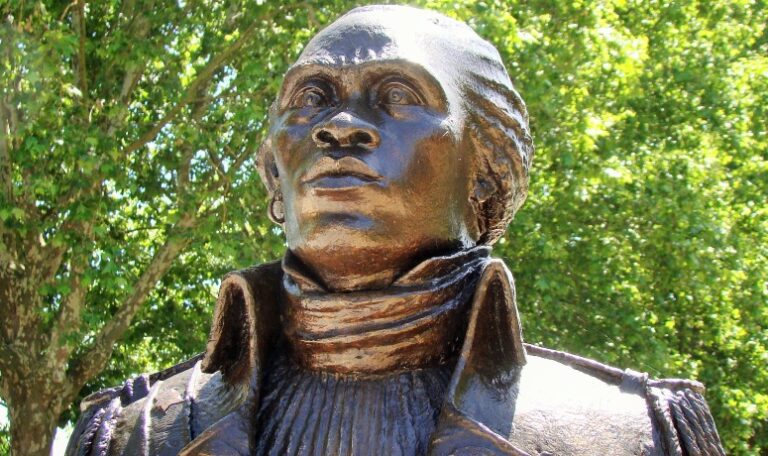

Chapter 1 – Culture and revolution: the story of Toussaint Louverture

How, then, was a slave-born man able to transform slave culture? How did Toussaint Louverture manage to organize an army of slaves in Saint Domingue (the name of Haiti before the revolution) and make it a fighting force so formidable that it was able to defeat Spain, England, and France, countries that held the greatest military power in Europe? How did this slave army inflict more casualties on Napoleon than he would suffer at Waterloo? Louverture was born a slave in Saint Domingue, on the Bréda sugar estate in 1743. Much of his personal history is ignored, only fragments of it are known because there was no concern to record the details of the slaves’ lives. Historians also disagree about most of the twists and turn in the Haitian Revolution, but agree that its leader was an extraordinary man.

As a teenager, he was put in charge of tending the mules and cattle at the mill, a job that a white man could do. Louverture took advantage of this rare opportunity and his free time to study and read all the books in his master’s library, including Julius Caesar’s Commentaries and Abbé Raynal’s History of the Two Indies, an encyclopedic account of trade between Europe and the Far East.

When Toussaint Louverture joined the army of the rebels, most of the soldiers wore no clothes. In the fields, they were used to working naked. To help turn this makeshift group into an army and make them feel like an elite fighting force, Louverture and his revolutionaries wore the most sophisticated military uniforms they had access to. Their clothing was a constant reminder of who they were and what they could achieve.

No culture can flourish without the enthusiastic participation of the leader. No matter how well defined, carefully programmed, and insistently demanded the elements that constitute it, an inconsistent or disingenuous way of behaving on the part of the one in charge undermines all these efforts.

Louverture understood this perfectly. He demanded a lot from his soldiers, but he was more than willing to be an example of what he demanded of them. He lived with the men in the army and participated in their work. When a cannon had to be moved, he helped drag it along and even had his hand crushed. He moved ahead of the troops in attacks, something Europe had rarely seen since Alexander the Great and was wounded seventeen times.

Chapter 2 – Application of the Toussaint Louverture case

Apple’s greatest strength has always been the integration between hardware and software. At its peak, the company had not paid much attention to common industry criteria such as processing speed and storage capacity but had been concerned with building products like the MacIntosh that encouraged people’s creativity. When it came to integration, Apple was better than any other company. This was due in part to its ability to control the entire product, from the user interface to the color of the hardware. Jobs did everything he could to keep employees in the company who understood this fact and who, like him, sought perfection in the user experience.

Jobs shrunk the product line to ensure that the company focused on delivering an amazing experience to human beings, not worrying about an impersonal set of specifications, speeds, and data transfer. When Apple was a laughingstock in the industry, it must have been tempting to completely dissolve the old culture. Gil Amelio, Jobs’ predecessor, tried to do just that. But like Louverture, the former slave who preserved the best of slave culture in his army, Jobs, the former founder, knew that the company’s original strengths had to be the foundation of a new mission.

Impactful Rules. These are the guidelines for creating a powerful rule that can give direction to the culture for many years to come:

– The rule should be easy to memorize. If people forget it, they forget the culture.

– It must prompt the question, “Why?” The rule must be so unusual and impactful that everyone should feel impelled to ask, “Is that serious?”

– Its cultural impact must be simple and direct. The answer to the question “Why” must clearly explain the cultural concept.

– The rule should be followed by people practically every day. If a rule only applies to situations that people face once a year, it is useless.

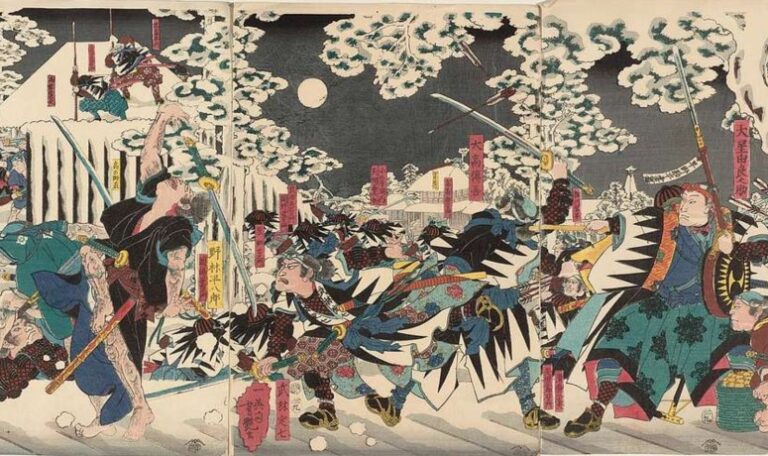

Chapter 3 – The path of the warrior

Bushidô seems like a set of principles, but in reality, it is a set of practices. The samurai defined culture as a code of action, not as a system of values, but of virtues. A value is just an abstract concept, but virtue is a concept that one seeks to apply or embody. And many efforts to create “corporate values” remain totally useless because more emphasis is placed on these values than on actions. From the point of view of culture, concepts mean nothing, because we are what we do.

The greatest threat to a company’s culture is a time of crisis, a period when we are being crushed by the competition or close to bankruptcy. How can we focus on the task we need to perform if we can be killed at any time. The answer: no one can kill someone who is already dead. If you have already accepted the worst possible outcome, you have nothing left to lose.

Modern companies tend to focus on objective data, such as targets, missions, and quarterly balance sheets. They rarely think about why employees show up to work every day. Is it because of money? Which is more valuable, the money or the time? My mentor Bill Campbell used to say, “We do it for each other. How much do you care about the people who work alongside you? Do you want to let them down?”

When Jim Barksdale became CEO of the company Netscape Communications in 1995, he knew he needed to change its culture. But how? By creating a cultural value? By getting people to disagree, but compromise? While disagreeing and compromising is an excellent rule of thumb for decision-making, it is not easy to introduce it into a culture that is used to doing the exact opposite.

Barksdale then came up with a story so memorable that it outlived the company itself. At an all-employee meeting, he said:

Here at Netscape, we have three rules. The first one is: if you see a snake, don’t form a committee, don’t call your colleagues, don’t organize a team, don’t call a meeting, just kill the snake.

The second rule is: don’t play with a snake that is already dead. Many people waste a lot of time with decisions that have already been taken.

And the third rule is: that every opportunity, at first, looks like a snake.

Chapter 4 – The warrior of a different path: the story of Shaka Senghor

One aspect that motivated me to write about Shaka Senghor is that it is very common for people who end up in prison to belong to a culture marked by conflict. Many have been victims of abandonment or beatings, or have been snitched on by their friends and are unable to do basic things, like keep their word. Prison is the hardest test for culture, and to build a culture in prison you have to start right from the beginning, from first principles.

James White (Senghor’s baptismal name) went to prison at the age when most people enter college. College culture introduces people to friendships, to brotherhood; prison culture introduced White to the extremes of violence and intimidation. He told me that when he went to jail he felt that from that moment on that would be his home.

The prison where White was was dominated by five gangs: the Sunni Muslims, the Nation of Islam, the Moorish Science Temple of America, the Five Percenters, and the Melanesian Islamic Palace of the Rising Sun (the so-called Melanics). The groups controlled commerce and offered their members protection and perks such as drugs, cigarettes, and better food, which included chicken and ground beef, for example, guaranteed by friends who worked in the kitchen. Any newcomer who did not integrate into one of these groups was vulnerable.

White joined the Melanics, a group that had formed in prison and adopted very particular principles borrowed from the Black Panthers and Malcolm X, including self-determination and education as the basis for black empowerment.

The code of the Melanesians was complex, but in essence, each member was responsible for all other members. If a person outside the group hit one of their members, the entire group would mobilize against that person, and they would not be safe in any prison. Anyone in the group who was a worthy brother had to be rescued, and that person’s fights would concern the entire organization. If a member of the group was deemed unworthy, which was usually when they refused to help another member, they would lose their protection.

Who is Shaka Senghor? A ruthless criminal, the leader of a gang of inmates, or the best-selling author and leader of prison reform who contributed to building a better society? It is clear that he is capable of being both. That is the power of culture. If you want to change who you are, you need to change the culture in which you live. Fortunately for the world, that is what he did, and what he did is who he is.

Chapter 5 – Applying the Case of Shaka Senghor

Two lessons for the leader can be highlighted from Shaka Senghor’s experience:

- The way you view culture is not very pertinent. Your view of how your executive team sees the company culture almost never corresponds to what employees actually experience on a day-to-day basis. Shaka Senghor’s experience on day one, coming out of quarantine, transformed him. The question that comes to mind is: what do employees need to do to survive and achieve success in your organization? Which behaviors put them on the power base and which ones exclude them? What gets them promoted?

- You have to start with the principles. Every ecosystem has its natural culture. (In Silicon Valley, our natural culture includes wearing casual clothing, employee participation in company ownership, and long work hours.) Don’t adopt it blindly. One prevailing culture may not be the best fit for your business. Make adaptations.

To understand the culture, it is best not to know what managers say, but to observe the behavior of new employees. What are the behaviors that, in their perception, will help them fit in, survive, and thrive in that environment? That is the culture of the company. Ask these questions directly to new employees at the end of their first week at the company. Also ask about the negative things, the practices or assumptions that make them suspicious or uncomfortable. Try to find out from them the differences between your company and other companies you have worked for, and not only what is better, but also what is worse.

Chapter 6 – Genghis Khan, master of inclusion

In 1206, the Mongol nobles gathered together and asked Temujin [Genghis Khan] to become their supreme leader. He accepted, but imposed some conditions: all Mongols should obey him without question, follow him wherever he went, and kill whoever he decided should be killed. When Temujin became the chief of 31 tribes and about 2 million Mongols, he adopted the name Genghis Khan, which means “fierce”, and “hard” ruler.

The Mongols were often divided. It was common for tribes and clans to unite to face common enemies, then split up and fight each other. All the nobles of the steppe, even the most vulgar gangster, believed that they should rule everyone. Genghis Khan realized that these warriors needed a common goal, which should not reflect the aristocrats’ dreams of primacy, but the soldiers’ most basic desires, and that he could motivate them with “an immense, exponential amount of war spoils,” in McLynn’s words. In effect, that would be their form of payment.

Mongol women were already treated exceptionally well for the time, but Genghis Khan abolished hereditary aristocratic titles and eliminated the caste hierarchy. Thus, all men became equal. Shepherds and camel drivers could become generals. Temujin called all his subjects “The People of the Felt Walls” – the material used for the walls of their dwellings (gers or iustas). This symbolized that they all formed one clan.

By transforming his army from a hereditary hierarchy into a true meritocracy, Genghis Khan managed to get rid of the idle and mediocre figures holding power in the aristocracy. Moreover, he improved the army’s performance and inspired soldiers to dream of leadership if they proved to be brave and intelligent.

Chapter 7 – Inclusion in the Modern World

American society often wonders, “Why do Fortune 500 companies have so few African-American CEOS?” The causes commonly pointed out are: racism, racial segregation, slavery, and structural inequality. Perhaps we should ask ourselves, “How did a boy raised in Chicago’s infamous Cabrini-Green Gardens housing development become the only African-American CEO of McDonald’s?” If we want to understand why inclusion doesn’t work, we ask the first question. If we want to understand how to make it work, we must ask the second. That boy is Don Thompson.

Don Thompson came to the top by taking a different approach: he embraced inclusion from the bottom up, forging alliances rather than forcing people to accept it. After he came to power, however, he employed techniques to promote equality very similar to those of Genghis Khan. Neither saw people through the prism of hierarchy or skin color, but rather as they were and what they could become if given the opportunity.

When Thompson was ten years old, he and his grandmother moved to Indianapolis. There, too, they went to live in an African-American neighborhood, but at school the majority were white. Rosa taught Thompson how to navigate these different worlds. She was a manager at Ayr-Way, a chain of retail markets that was later acquired by Target. Most of her employees were white, but Grandma treated everyone the same, and everyone came to her house to visit. Grandma Thompson learned that there are good people and bad people and that you have to analyze each one individually to figure out who is good or bad.

Inclusion is a broad and complex issue, and I am not qualified to talk about its social aspects. So I will focus only on how to apply the principles of Gengis Khan, Don Thompson, and Maggie Wilderotter to give a company a competitive advantage by attracting the best talent available. By seeing people as they really were, they were able to see what they actually had to offer.

Chapter 8 – Be yourself and create your culture

Every CEO has aspects of his or her personality that they or prefers not to see reflected in the company. Think, and evaluate what your flaws are, to prevent them from reflecting in your company’s culture. Otherwise, the act of leading by example may turn against you.

One of the aspects of my personality that did not work very well in a software company was my habit of engaging in seemingly endless, baseless conversations. (This fits better in a venture investment company.) Tip for my future friends: if you don’t put an end to our phone calls, we may talk forever and ever.

When you feel good about yourself, you can start to make part of your identity reflect the culture you want to create in the company. When Dick Costolo became CEO of Twitter, his adviser Bill Campbell jokingly said that if a bomb exploded in the company at five o’clock in the afternoon, only the cleaning staff would die. Costolo wanted to change the culture, to encourage hard work, because he himself is used to working hard. After dinner with his family every evening, he would go back to the office and make himself available to whoever was still there and wanted his help with anything. Soon a large number of people were working longer and producing more. If Costolo had not been able to concentrate and work efficiently for a long time, his plan would never have worked.

Chapter 9 – Borderline cases and practical lessons

Cultural rules can become sacred cows, huge and useless. Everyone treads on eggshells around them try to respect the culture – but suddenly the cows fall on you and crush you. Strategies get better, circumstances change, and you learn new things. When this happens, you have to change the culture. Otherwise, you will end up suffocated by it.

I had seen something in analyst Connie Chang that I almost never see. She answered all the questions, she gave a surgical analysis of the company, and she revealed an elegance that was second to none… Chan was determined to be the best at whatever she did, she was destined to be great. I understood all that, but I couldn’t say.

I couldn’t tell you because I immediately perceived a conflict between her irresistible strength and our policy of not promoting anyone from within the company. Since we could not promote Chang as the partner, one day she would inevitably leave. As she performed over the years, closing spectacular deals like Pinterest and LimeBike, all I could think about was the day she would leave us. Still, it never crossed my mind to change the rule, because anyway…it was a rule.

One day our team was evaluating membership candidates, and Jeff Jordan, one of our partners, said, “I would prefer Connie to any of these candidates.” I replied, “But she doesn’t meet our criteria.” Everyone was silent, but that silence spoke loudly. The stuff of culture is actions. If actions don’t work, it’s time to adopt new actions. We promoted Connie to partner in 2018 and she is killing it.

Chapter 10 – Final Thoughts

Are you a sincere and outspoken person? I bet you stopped for a moment to think about it and then answered, “Yes.” Who else do you know that you consider sincere and outspoken? I bet it was much harder to answer that question. How is it possible that everyone considers themselves sincere, but has such a hard time identifying other sincere people?

There are several reasons why people are not sincere and open. However, there are also ways to gain their trust. One of them is: focus on the problems, not the people. If you identify a problem, look for the main reason that caused it. Most likely you will find that the underlying problem was communication, prioritization, or another cause that has a solution, not that it was caused by a negligent or short-sighted employee. By identifying what caused the problem and solving it, rather than placing the blame on one or two employees, you avoid a culture of secrecy or a defensive attitude and create a culture of openness to bad news.

Conclusion

Culture starts when you decide what is most important. Then you need everyone in the organization to adopt behaviors that reflect those virtues. If they prove ambiguous or even counterproductive, you need to change them. If it is clear that your culture lacks essential elements, you need to incorporate them into it. Finally, you should pay close attention to the behavior of your employees, and even more attention to your own behavior. How is their behavior affecting your culture? Are you the person you would like to be?

This is how you create a great culture. This is how a great leader acts.

FACTSHEET:

Title: What You Do Is Who You Are – How to Create your Business Culture

Author: Ben Horowitz

Photos: Jefunky, Gary Todd, Joi Ito / Wikimedia Commons; Picryl

Review: Rogério H. Jönck

![[Experience Club] US [Experience Club] US](https://experienceclubus.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/laksdh.png)

![[Experience Club] US [Experience Club] US](https://experienceclubus.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/logos_EXP_US-3.png)