The official TED guide to public speaking, written by Chris Anderson, the former editor-in-chief of Wired who bought and is now the chief curator of the lecture platform

Central Ideas:

1 – The central thesis of this book is that anyone with a worthwhile idea is capable of delivering an effective talk. The only thing actually important when speaking in public is not self-confidence or the gift of “speaking well”. It is having something important to say.

2 – To deliver an effective lecture, you need to narrow the range of subjects covered down to a single, cohesive thread – a master line that can be developed appropriately. In a sense, you will cover fewer points, but the impact will be far greater.

3 – There are two types of tests: the human and the technical. For the human, it is recommended that you test the presentation – especially the slides – with relatives and friends who do not work in your field. Then ask them what they understood or didn’t understand, or if they have any questions.

4 – Look for “friends” in the audience. At the beginning of the lecture, look for faces that seem friendly to you. If you find three or four at different points in the audience, address your talk to them. If you find real friends, even better.

5 – The simplest way to give an effective lecture is to stand up, distribute your body weight equally on both legs – keeping your feet a little apart – and use your hands and arms to amplify what you are saying naturally. Then just welcome the applause.

About the author:

Chris Anderson is president and chief curator of TED. He worked as a journalist after graduating from Oxford University and launched more than a hundred magazines and websites before turning his attention to TED, purchased by him and his nonprofit organization in 2001.

PROLOGUE

The purpose of this book is twofold: first, to explain how the miracle of effective public speaking is performed; and second, to help you do it in the best possible way. However, one thing must be emphasized at the outset. There is no single way to give a high-level speech. The world of knowledge is too wide and the range of speakers and audiences too varied. Any attempt to apply a predefined formula will probably backfire. The audience realizes this on the spot and feels manipulated.

So don’t judge the advice in this book as rules that prescribe a single way to speak. Instead, think that the book is offering you a set of tools that seek to encourage variety. Use the ones that are convenient for you and for the talk you are about to give. Your only real obligations when giving a talk are to have something important to communicate and to come across as authentic in your own way.

In the 21st century, communicative competence should be taught in every school. In fact, before the age of books, it was considered an essential part of education, albeit with an old-fashioned name: rhetoric. Today, in the connected age, we should resurrect this noble art and make it one of the foundations of education: reading, writing, mathematics… and rhetoric.

The word “rhetoric” simply means “the art of speaking effectively.” That is the fundamental theme of this book. To recast rhetoric for the modern age. Providing useful contributions to a new communicative competence.

Our experience with TED over the course of the last few years can help point the way. TED began as an annual conference, with talks in the fields of Technology, Entertainment and Design (hence the name). In recent years, however, the program has expanded to cover any topic of public interest. The speakers try to spread their ideas to people who are not active in their field, and to this end they deliver carefully prepared short talks. To our satisfaction, this form of public speaking has proved to be a resounding success online: today TED talks count more than a billion views a year.

BACKGROUND

Getting up on a stage where hundreds of pairs of eyes are nailed on you is terrifying. You dread standing up in a company meeting and presenting your project. What if you screw up and stumble over your words? What if you completely forget what you intended to say? This can create a humiliating situation. Or even end your career. And, who knows, the idea you believe in may never get out.

TED Conference participants have told us wonderful anecdotes about the impact of their words. Sometimes there are proposals for books and films, as well as unexpected offers of financial support. However, the most interesting stories are linked to the promotion of ideas and life changes. Amy Cuddy gave an extremely popular talk on how changing body language can increase self-confidence. She received over fifteen thousand messages, from people all over the world, telling how she had benefited.

I will now tell you a personal story. When I took over TED in late 2001, I was recovering from the near collapse of the company I had spent fifteen years building. I was terrified of the possibility of another huge public failure. I had been struggling to convince the TED community to support my vision for the program, and I feared that this struggle would come to nothing.

I spoke from the heart, with the utmost frankness and conviction. I said that I had just suffered a violent business failure. That I had come to consider myself a complete failure. That the only way I could survive mentally was to dive into the world of ideas. That TED had come to mean everything to me – that it was a unique space where ideas from all disciplines could be shared. That I would do everything in my power to preserve its best values. That, in any case, the program had provided us with so much motivation and so many subsidies that we could not let it die, right?

To my utter amazement, at the end of the talk, Jeff Bezos, chairman and CEO of Amazon, who was sitting in the middle of the audience, stood up and began to applaud. And everyone else followed. It was as if the TED community had collectively decided in a few seconds that they would support this new chapter of the program after all. Then, in the sixty-minute interval that followed, about two hundred people pledged to sign up for next year’s lecture series, ensuring its success.

Start with the idea. The central thesis of this book is that anyone with a worthwhile idea is capable of delivering an effective lecture. The only thing really important when speaking in public is not self-confidence, stage presence, or what is commonly called “speaking well.” It is having something important to say.

I am using the word “idea” in a very broad sense. It doesn’t have to be a scientific breakthrough, a genius invention, or a complex legal theory. It can be a simple set of instructions on how to do something.

Learning Wednesday. In 2015, we ran an experiment at TED headquarters. Every two weeks, we gave everyone on the team a day off to devote to studying a certain subject. We called that day Learning Wednesday. The idea was that since the organization is about lifelong, continuous learning, we should practice what we preach and encourage all team members to take the time to study what interests them. But how do we prevent this Wednesday from becoming just a day with nothing to do, spent in front of the TV? Well, there was one more thing: everyone had to commit to giving a TED talk at some point during the year about what they had learned to the rest of the organization. Fine, but you don’t need a special Wednesday to learn how to speak. Speak in front of groups that respect you and you will see that you can make progress.

The key principle is to remember that the speaker should make a gift to his listeners, not take something from them. People don’t go to a conference to listen to sales pitches. When they realize that this may be the speaker’s intention, they flee to the safety of their e-mail boxes. It is like accepting a banker friend’s invitation for coffee and realizing, with great irritation, that she really wants to convince you to invest money in a savings plan.

In the first TED talk series I organized, one of the speakers started talking like this: “As I was driving here, thinking about what I would say to you…” And a series of scattered observations about possible futures followed. Nothing too boring or especially difficult to understand. But no thought-provoking arguments, no revelations, nothing was assimilated. Many lectures are like this. Winding, with no clear direction. A lecturer can delude himself and convince himself that even a riotous exploration of his brilliant ideas will be fascinating to the audience. But deluding eight hundred or more people is more complicated and… useless.

The goal of a lecture is to say something meaningful; it is amazing how many lectures fail to achieve this goal. Indeed, many things are said in them. But for one reason or another, the audience doesn’t get anything they can take away with them. However, there are ways to captivate the audience. A good exercise is to summarize your keynote in no more than fifteen words. And they need to offer vigorous content. It is not enough to think of your goal in terms of “I want to motivate the audience” or “I want to get support for my work. Your keynote needs to have more focus than that. Here are some guidelines from successful TED talks:

The potential of education is transformed when we focus on children’s extraordinary (and hilarious) creativity.

A story of the universe in eighteen minutes shows a path from chaos to order.

The combination of three simple technologies creates an uncanny sixth sense.

I almost died on a trek to the south pole, and it changed my sense of purpose.

However, a guideline that connects many concepts does not work. There is a serious consequence when you go too fast through several subjects: they don’t make an impact. You know the background and context of what you are saying, so the information seems more than enough to you. However, the audience is having contact with your work for the first time. Therefore, the talk will probably seem fragmented, dry, or superficial.

The right way. To deliver an effective talk, you need to narrow down the range of subjects covered, reducing it to a single, cohesive thread – a main line that can be adequately developed. In a sense, you will cover fewer points, but the impact will be substantially greater.

The TED speaker with the most views on the Internet at the time this book was written was Sir Ken Robinson. According to him, in general, his talks follow a simple structure:

Introduction – introduction, what will be exposed

Context – why the issue is relevant

Key concepts

Practical implications

Conclusion

LECTURE TOOLS

Listening to a lecture is something completely different from reading an essay. It is not just about the words, but rather about the person who utters them. For them to cause astonishment, there must be human harmony. You can give a brilliant lecture, with crystal-clear explanations and unassailable logic, but if you don’t first of all get in tune with the audience, it doesn’t fulfill its purpose. Even if the content is understood to some extent, it will not be activated, but filed away in some mental folder about to be forgotten.

At TED, our number one advice to speakers on the day of the presentation is to regularly make eye contact with the audience. Demonstrate warmth. Demonstrate truthfulness. Don’t try to be someone else. This will make them trust you, like you, and begin to share your passion.

Indeed, for many great speakers, humor has become a powerful weapon. Sir Ken Robinson’s talk on the failure of schools to encourage creativity, which by 2015 was getting close to 35 million views, took place on the last day of the presentation cycle. He began like this, “That was pretty cool, wasn’t it? I got kicked out of the corner. I’m actually leaving.” The audience giggled a little. And it didn’t stop any more. From then on, he won us over. Humor dispels the main resistance to listening to a lecture. By making small concessions to laughter right from the start, you are subtly cheering up your audience… let’s go, my dear friends. It’s going to be a blast.

Audiences that laugh soon come to like the speaker. And if they like the speaker, they will be much more willing to take what is said seriously. Laughter breaks down defenses, and suddenly you have a chance to really communicate with the audience.

The fire created a new stimulus for social bonds. Heat and light brought people together at nightfall. This seems to have occurred in all ancient hunter-gatherer cultures over the last three hundred thousand years. And what did they do during their time together? Apparently, one form of social interaction became prevalent in many cultures: storytelling.

Simplify the focus. Some of the best lectures are built around a single story. This structure generates enormous benefits for the speaker:

It creates the storyline. (It is simply the narrative arc of the story.)

If the story is engaging, you get an internal reaction from the audience.

If the story is about you, you create empathy for some of the things you hold most dear.

You don’t forget what you are going to say because the structure is linear, and it is very easy for your brain to remember facts in sequence.

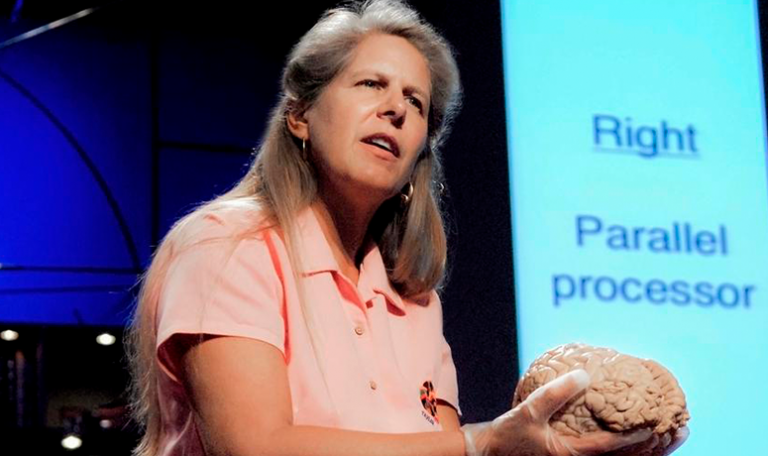

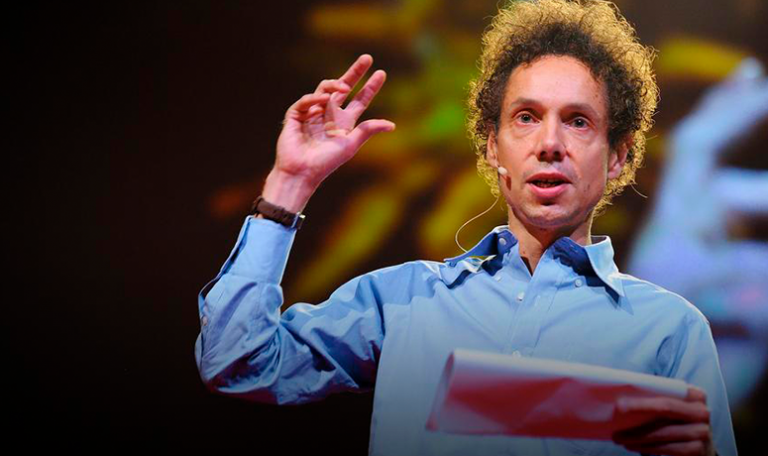

Journalist Malcolm Gladwell also specializes in parables, and the appeal of this story form is reflected in the impressive sales of his books and the high number of views of his lectures. His most viewed word, believe it or not, is a story about the creation of spaghetti sauce shapes. But he uses it as a parable for the idea that people want very different things, but often don’t have the words to express what they want, until you ask them the right questions.

Tuning, narration, explanation, persuasion… they are all vital tools. However, what is the most direct way to present your idea to an audience?

Simply by showing it.

Many lectures are based on this model. You reveal your work to the audience in an enjoyable and inspiring way. The generic name for this is a revelation. In a revelation-based lecture, you can:

Show a series of images of a new art project and talk about it.

Demonstrate a product you have invented.

Describe a vision of a self-sustaining city of the future.

Show fifty amazing photos from your recent trip to the Amazon rainforest.

But wonder walks work when there is a clear theme linking the steps, something stronger than a mere succession of recent examples of his work. Without that, this kind of lecture can easily become boring. “Now let’s see my next project” is a dull transition line that invites the audience to wiggle in their chair. By showing a connection, it gains much in strength: “This next project takes up the idea and surpasses it in vigor…”

At TED, most of the talk is done in more colloquial language. However, the ability to paint a compelling picture of the future is one of the greatest gifts a speaker can offer. Indeed, speakers who are able to show a dreamscape are among the most exciting at TED. They speak not of the world as it is, but as it could be. The sense of possibility generated by a well-crafted dreamscape is capable of melting minds and making hearts beat harder.

PREPARATION PROCESS

Photographs, illustrations, proper typography, graphics, infographics, animations, videos, audios, and data simulations: all these elements can enhance both the informational level and the aesthetic appeal of a lecture.

However, the first question to ask is: is there really a need to use any of these features? It is remarkable that at least one third of the most viewed TED Talks on the Internet do not have a single slide.

Surely this is not a dispute for attention between the screen and the speaker. Often, what is shown on the screen occupies a different mental category than what is being said. A case of aesthetics versus analysis, for example. Nevertheless, if the essence of your talk is intensely personal, or if you have other means of enlivening it – such as humor or interesting stories – you may want to leave visuals aside and concentrate only on speaking to the audience in a personal tone.

And for all speakers, the following principle always holds true; better no slide than a bad slide.

Tips on software. In 2016, there are three main tools for presentations: PowerPoint, Keynote (for Mac), and Prezi. PowerPoint is the most common, although I think Keynote is easier to use and has better typographic fonts and graphic elements. Prezi (an application of which TED was one of the first investors) has an alternative mode in which, instead of a linear succession of slides, you move through a two-dimensional landscape, zooming in or out on what interests you.

There are two types of test: the human and the technical. For the human test, I recommend that you test the presentation – especially the slides – with relatives and friends who do not work in your field. Then ask them what they understood, what they didn’t understand, and if they have any questions. Testing is essential, especially on very technical subjects.

Technical testing is also key. I have a Kensington remote control that can be plugged into the USB input of your computer, so I can click during the lecture, just as I would on stage. Are the slides crisp and clear? Are the transitions fast enough? Are the fonts correct? Are the videos playing well? Are there technical problems of any kind? And running through your talk several times will help you know if it is okay.

A few years ago TED was very strict about the rules for talks: no pulpit. Never read your talk. And in general these rules made sense. People react well to the vulnerability of a speaker who stands there unprotected, without a pulpit, talking from memory. It’s the purest form of personal communication.

But variety also has its strength. If every speaker stood in the middle of the stage, enunciating with vibrant clarity a perfectly decorated word, the audience would soon tire. When a group of people mobilizes for a week of lectures, the most impactful speakers are those who do things in a different way. If everyone speaks without a script, the eccentric professor who casts squinting glances at a pulpit to read the lecture may well be the one to stick in the memory.

And above all, what matters is that the speakers feel comfortable and confident, delivering their presentation in the way that best allows them to focus on the subject that excites them.

Advantage of the script. The biggest advantage of going with a script is that you can make the best use of the time. It can be very difficult to condense everything you want to say into ten, fifteen or eighteen minutes. If complicated explanations are needed, or important steps in your persuasion process, you may need to select every word and fine-tune every sentence or paragraph. The scripted lecture has another advantage: we can share it in advance. We love it when speakers send us an outline of what they are going to say two months before the lecture cycle. This gives us time to comment on which elements can be cut and which perhaps need more detailed explanation.

To tell you the truth, the old method of cards with brief handwritten notes is still an acceptable way of keeping track. Use words that evoke key phrases, or lines that move you forward to the next step in the talk.

One thing to keep in mind is that the audience will not mind if you pause to take stock of the situation. You may feel some discomfort. They won’t. The key is to relax. When DJ star Mark Ronson participated in TED2014, he was exemplary in this regard. At one point he got lost, but he simply smiled, walked over to a bottle of water, took a sip, told the audience that that was his mental crutch, examined his notes, and took another sip of water. When he started again, everyone was liking him more than ever.

Whichever way you speak, there is a very simple and obvious tool that can improve your talk, but that most speakers rarely use: rehearse. Often.

Musicians rehearse before they play. Actors rehearse before the theater doors open to the paying public. In the case of the lecture, the stakes are as high or higher than in any concert or play, yet many speakers act as if they think they can just go on stage and everything will work out right the first time. This is why, time and again, simply because someone has not prepared adequately, hundreds of listeners have to endure endless minutes of unnecessary distress. Regrettable.

The greatest corporate communicator of recent times, Steve Jobs, did not get there by talent alone. He devoted hours to careful rehearsals to launch every major Apple product. He was obsessed with detail.

Summary of the opera:

For an important talk, rehearsing several times is key, preferably in front of trusted people.

Work on it until it fits loosely into the time you have been given, and insist on honest feedback from the rehearsal audience.

Your goal is to arrive at a lecture whose structure becomes something internalized so that you can concentrate on the content of what you are saying.

Stimulating curiosity is the most versatile tool you have at your disposal for securing the audience’s attention. If the goal of the talk is to instill an idea in the listeners’ minds, curiosity serves as the fuel that energizes their active participation.

How to provoke the spark of curiosity? The most obvious way is to ask a question. But not just any question. It has to be a surprising question.

How to build a better future for all? Too broad. Too cliché. I got bored already.

How did this fourteen-year-old girl, with less than two hundred dollars in her bank account, make her town take a giant leap into the future? Now the story has changed.

It is right to save the big revelations for the middle or end of the presentation. In the opening sentences, its sole purpose is to give the audience a reason to leave their comfort zone and follow their amazing expedition of discovery.

As J. J. Abrams reminds us in his talk on the power of mystery, much of the impact of Jaws is due to a choice made by director Steven Spielberg, who kept the monster hidden throughout the first half of the film. Of course you knew you were going to see him, but the invisibility kept the tension going.

ON THE STAGE

It is worthwhile to rehearse your lecture wearing the clothes you will wear on the day. I remember a speaker whose clothes fell off at the beginning of her presentation. The straps of her bra fell off and hung down her arms during the speech. Our image editors managed to work some magic, so in the video, it is not noticeable, but this would be avoided with a costume rehearsal and pins.

I repeat: the most important thing is to wear something that reinforces your safety. This is something you can fix in advance. And it will be one less thing to worry about and one more thing to work in your favor.

Use fear as motivation. That’s what it’s for. It will make it easier for you to make a real commitment to rehearse the lecture as many times as necessary. Your confidence will increase, your fear will decrease, and your talk will be better.

Let your body help. Before you go on stage, there are a number of important things to do that help to bypass the adrenaline rush. The most important is to breathe. Deep breathing, as in meditation. The oxygen calms you down. You can do this even in the audience while waiting for your call. Take a deep breath in through your diaphragm and let the air out slowly. Repeat three times. If you are out of sight of the audience and feel the tension building in your body, you may want to try more vigorous physical exercise.

Look for “friends” in the audience. At the beginning of the lecture, look for faces that seem friendly to you. If you find three or four at different points in the audience, address your talk to them, looking from one to the other. Everyone will see the harmony, and the encouragement you will discover in these faces will give you calm and assurance. Maybe you can get some of your real friends into the auditorium. Speak to them. (Besides, speaking to friends also helps you find the most appropriate tone.)

Maybe your notes won’t fit on a single sheet. You want to remember every slide transition, the examples that accompany each main topic, or the exact closing text. In this case, it may be best to use a set of cards and flip through them one by one. It is best to secure them with a clip to prevent them from going out of order if they are dropped. These cards are almost invisible and allow you to check where you are in the lecture. The only drawback is that you only have to consult them a few times, and when you want to find a topic, you have to go through five or six cards to get to what you are looking for.

One of the reasons I became enamored with TED was that I realized that lectures done right could provide something more that you simply cannot extract from the printed word. However, this does not fall from the sky, nor does it apply in all cases. You have to think about this something more, invest in it, develop it. You have to conquer it.

But what is this something more? It is the human dimension that turns information into inspiration. Here are some effects that this extra dimension can have:

Attunement: I trust this person.

Involvement: Every sentence sounds so interesting.

Curiosity: I understand what you mean in your voice, and I see it in your face.

Conviction: So much determination in that look.

Action: I want to be part of your group. Count on me.

Use the body. The simplest way to give an effective speech is to stand up, distribute your body weight equally on both legs – keeping your feet a little apart – and use your hands and arms to amplify what you are saying naturally. If the layout of the audience is somewhat curved in relation to the stage, turn your waist slightly to address the different parts. There is no need to walk back and forth. This choice can convey serenity and authority; it is the method used by most TED speakers, among them Sir Ken. The key is to relax and let the upper body move at will.

Illustrated interview. An interview can be a good alternative to a lecture. It gives you the opportunity to do two things:

Explore a variety of topics without having a single master line, other than the life and activity of the speaker; and

Encourage the speaker to go deeper than he would normally go in a conventional lecture. (This is especially true of high-profile speakers, whose public presentations are generally written by their communications department).

At TED we have experimented with an interview format that encourages preparation from both the interviewer and the interviewee, while allowing for the enthusiastic expression of different opinions that is common in traditional interviews. This is a conversation accompanied by a sequence of images prepared beforehand by both.

Generally speaking, we do not recommend presentations by more than one speaker. For one reason or another, the audience seems to find it more difficult to get in tune with more than one speaker on stage. People don’t know who to look at and may end up not connecting deeply with any of them. However, there are occasions when the interaction between speakers creates a vivid and authentic effect. This was the case when Beverly and Dereck Joubert wrote about their lifelong work with leopards and other wild cats: the affection and respect evident between the two moved the audience.

More about TED

June Cohen joined our fledgling group, and we engaged in what seemed the logical strategy for sharing TED content more widely: taking it to television. All the talks given up to that point had been videotaped, and with so many cable channels, no doubt someone would be interested in airing a weekly presentation. We produced a pilot in June 2005, which we excitedly showed to anyone who wanted to see it. The resounding verdict of the TV world: total indifference.

In November 2005 June came to me with a radical proposal: to leave TV aside for the time being and try to broadcast the TED videos on the Internet. And that is how, on June 22, 2006, the first six TED Talks debuted on our website. At the time, ted.com was getting about a thousand hits a day, mostly for details about past or upcoming presentations. On the first day we had about ten thousand views. I imagined that, as is usually the case with new vehicles, once the initial interest had passed, the number would soon drop. The opposite happened. Only three months later, we had reached one million views, and the numbers kept rising.

Almost ten years later, interest in TED Talks spread around the world. To our surprise and joy, they have become a global platform for identifying and disseminating ideas, thanks to the efforts of hundreds of speakers, thousands of volunteer translators, and tens of thousands of local event organizers. By the end of 2015, the lectures totaled one hundred million monthly views – 1.2 billion per year.

In 2009 we began to offer a free license to anyone wishing to organize a TED-style event in their city. We use the label TEDx in such cases, where x indicates that the event is independently organized, and refers to the multiplying effect of the program. To our satisfaction, thousands of people have organized TEDx events. More than 2,500 take place each year in over 150 countries.

Tip

You can find the events held or apply to organize your own at http://ted.com/tedx.

Review: Rogério H. Jönck

Photos: reproduction

FACTSHEET

Title: TED Talks – The official TED guide to public speaking

Original Title: TED Talks: The Official TED Guide to Public Speaking

Author: Chris Anderson

![[Experience Club] US [Experience Club] US](https://experienceclubus.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/laksdh.png)

![[Experience Club] US [Experience Club] US](https://experienceclubus.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/logos_EXP_US-3.png)