A guide to making what’s most important easier and achieving success without having to die from working so hard

Central Ideas:

1 – Inversion means turning an assumption upside down, asking “What if the opposite were true?” Inversion can help you realize obvious insights that you missed because you saw the problem from a single point of view.

2 – When we are present with people, we make an impact. And not just in that moment. The experience of feeling like the most important person in the world, even for a brief moment, can stay with us for a long time, disproportionate to that moment.

3 – Being clear about the aspect of a project to be completed is not only helps us finish, but it also helps us get started. We often procrastinate or have difficulty taking the first steps in a venture because we don’t have a clear finish line.

4 – The beauty of the checklist is that the thinking has been done in advance. It was taken out of the equation. Or, rather, it was built into the equation. So instead of getting those essential things right once in a while, we get them right every time. And we avoid accidents.

5 – Trust is the soul of the team. Warren Buffett uses three criteria to determine who is trustworthy to be hired or to sit at the negotiating table with him. He looks for people with integrity, intelligence, and initiative. But with a lack of the first, the other two backfire.

About the author:

Greg McKeown lectures worldwide on the importance of living and leading as an essentialist. In addition to this book, he is the author of the best-selling book Essentialism. He is one of the creators of Stanford University’s Designing Life Essentially course. He is a global young leader for the World Economic Forum.

Introduction

All of a sudden, Patrick McGinnis, an expert on work and entrepreneurship and a writer, realized that the balance of overwork was negative.

What could he do? He could continue in the same old way and probably die from working too hard; he could lower his expectations and give up his goals, or he could find an easier way to achieve the success he wanted.

He chose the third option.

He resigned from AIG but continued to work as a consultant. He stopped working 80 hours a week. He started coming home at five o’clock in the afternoon. He didn’t read or send e-mails on weekends.

He also stopped treating sleep as a necessary evil. He started walking, running, and eating better. He lost eleven kilos. He started to enjoy life again and to enjoy his work.

Have you felt that you are running faster, but are not getting closer to your goals? Do you want to make a contribution, but can’t because you lack energy? Do you have the feeling that you are one step away from physical and mental exhaustion? Do you realize that the situation is much more difficult than it should be?

If you answer “yes” to any of these questions, this book is for you. It would be unrealistic to claim that this book has the power to remove those tribulations. I didn’t write No Effort to underestimate the weight of your afflictions but to help you make them lighter. It may not make every difficult burden easier to bear, but I believe it can uncomplicate many things.

Strangely enough, some people react to exhaustion and overload by promising to work even harder. It does not help that our culture glorifies physical and mental exhaustion – or burnout syndrome – as a measure of success and personal worth. The implicit message is that if we do not feel perpetually exhausted, it is because we are not doing enough. According to this mindset, great achievements would be reserved for the bleeding, the ones who come close to collapse. Overwhelming volume should be the goal.

I strove to be a model essentialist [I had written the book Essentialism]. To live according to what I taught. But it wasn’t enough. I could feel the flaws in the assumption I had always clung to: that in order to get everything we want without getting too busy or forcing ourselves into the impossible, it was enough to have the discipline to only say “yes” to essential activities and “no” to everything else. But now I wondered what to do when life is already reduced to the essentials and there are still too many things.

PART ONE – Effortless State

The basketball player with the best free-throw shooting record is not Michael Jordan or Steph Curry. It is Elena Delle Donne. Her success rate at the free-throw line during her career is 94.4%. It is the highest in the history of both the women’s (WNBA) and men’s (NBA) American leagues.

And what would be the most important part of the process? “Not overthinking it. The most important thing at the free-throw line is not to let too many things get into your head.”

In other words, the secret to Elena’s success is the ability to achieve what I call the Effortless State.

Kim Jenkins wanted to do what was really important, but she was overwhelmed. For one thing, the university where she worked was undergoing a major expansion. The client base had doubled in recent years, but they were operating with virtually the same number of staff and resources as before. As a result, the effort required to do his job had become Herculean.

But one day it hit him. A huge task came to him. To record an entire semester of a course.

A quick conversation revealed that the videos would be for a single student who could not attend class due to sports commitments. He did not need a very well-produced recording, full of sound and image resources. So she thought, what if the teacher simply asked another student to record the lessons with his cell phone? “He was very pleased with the solution,” Kim said. And it only took him a few minutes of planning instead of months of work by the entire audiovisual team.

The language also betrays our distrust of ease. When we talk about “easy money,” we imply that it was obtained by illegal or questionable means. We use the expression “easy talk is easy” as criticism, usually when we seek to invalidate someone’s opinion.

Inversion means turning an assumption or approach upside down, working backward, asking “What if the opposite were true?” Inversion can help you realize obvious insights that you missed because you were viewing the problem from a single point of view. It can highlight the errors in your reasoning. It can open your mind to new ways of thinking.

Comic Relief is best known for Red Nose Days, which first took place in February 1988. More than 150 comedians and celebrities took part in the televised event, which attracted 30 million viewers: more than half the population. People from all corners of the UK bought red noses, and the proceeds went to charity

Giving to charity is important. Attending a comedy day is enjoyable. By bringing charity and comedy together, Jane Tewson has made it easy for the charity fact. As a result, people not only participate but actually look forward to participating again year after year.

But essential work can be pleasurable if we let go of the puritanical notion that anything worth doing needs to require strenuous effort. Why do we simply endure essential activities when we can enjoy them? By combining essential activities with enjoyable ones, we can make it effortless to perform even the most boring and unbearable tasks.

When we associate small fragments of wonder with mundane tasks, we no longer wait for the time when we will finally allow ourselves to relax. That time is always now.

When fun and play light up our daily lives more often, we move closer to our natural Effortless State.

We live in a culture of complaint that is intoxicated by expressing its outrage – especially on social media, which seems like an endless stream of complaints and grumblings about what is unsatisfactory or unacceptable. Even if we don’t engage in it directly, it can still affect us. In large amounts, the whining of others gives us emotional cancer. We begin to perceive more injustices in our life. These are the “little ghosts” occupying valuable space in our brains and heart.

The extend and build a theory of psychology explains how this happens. Positive emotions open us up to new viewpoints and possibilities. This openness encourages creative ideas and promotes social bonds. These things transform us. They unlock new physical, intellectual, psychological, and social resources. They create an “upward spiral” that increases the likelihood that we will cope well with the next challenge we face.

However, Joe Maddon [baseball coach] sees an advantage in the art of doing nothing. He implemented this idea by changing his players’ routines during “American Legion Week,” which takes place during the hot days of August when players’ performance is usually down. Instead of piling up hours of pre-game training, he tells his players not to arrive until match time. He encourages them to sleep late, take naps, and arrive rested, the same way they did when they were teenagers as amateurs.

Maddon’s approach has had a transformative impact not only on the Angels but on the other teams he has coached over the past decade.

The easiest way is to continually discharge our physical and mental energy by taking short breaks. Plan these breaks throughout the day. That way, we will be like those high-performance individuals who take advantage of the body’s natural rhythm.

To do this, try the following:

Devote your mornings to essential work.

Break it down into three sessions of no more than 90 minutes each.

Take a short break (10 to 15 minutes) between sessions to rest and recover.

No relationship is effortless, but there is an easier way to keep it solid. We don’t have to agree on everything with the other person. But we do have to be present with them, really notice them, give them our full attention – maybe not always, but as often as possible.

When we are fully present with people, we make an impact. And not just in that moment. The experience of feeling like the most important person in the world, even for a brief moment, can stay with us for a disproportionate amount of time after the moment has passed. There is a curiously magical power in presence.

SECOND PART – Effortless action

Larry Silverberg is a “dynamicist,” that is, an expert on the movement of physical things. For example, he has studied for 20 years the motion of millions of basketball free throw shots.

One thing that Larry discovered during this period was that the most important factor for success at the free throw is the speed with which you release the ball. Achieving the ideal synesthetic condition requires training and muscle memory. The goal is to reach the point where movements become fluid, natural, and instinctive.

This is what Effortless Action means.

Once we get past a certain point, more effort does not produce better performance. Instead, excess sabotages the result.

Overexertion occurs when we push too hard or try “too hard. Perhaps you have experienced this. Trying too hard in a socializing environment prevents you from authentically connecting with another person. Trying too hard for a promotion can seem desperate, and therefore make you less desirable. Trying too hard to sleep can make it almost impossible to relax. Trying too hard to look smart rarely impresses the people you want to impress. That’s the problem with trying too hard.

Having clarity about what a finished project looks like not only helps us finish, it also helps us get started. We often procrastinate or have difficulty taking the first steps in a venture because we don’t have a clear finish line in mind. Once you define it, you will give the conscious and unconscious mind an unambiguous instruction. Things will fall into place and you will be able to map out the trajectory toward that end state.

The concept was big – huge, in fact. It was ambitious and long-term. The founders knew what the “finished aspect” would look like – the huge global streaming service and content library that Netflix is today – but instead of mapping out a complex, detailed plan to get there, Reed Hastings and Marc Randolph looked for the ridiculously simple first step that would inform them whether to take the second step or give up. Sending that single CD was the simplest and most obvious way to set their grandiose idea in motion.

You don’t need to feel overwhelmed by your essential projects. Focus on the obvious first step and you will avoid spending too much mental energy thinking about the fifth, the seventh, or the twenty-third step.

A fundamental tenet of Silicon Valley thinking – and, more broadly, design thinking – is the practice of developing a minimum viable product. Eric Ries, the author of The Lean Startup, defines the minimum viable product as the “version of a new product that allows the team to collect the maximum amount of validated learning about customers with the least amount of effort.” It’s an effortless way to test an idea because it only requires building the simplest version of the product, just what’s needed to get reliable feedback that customers want.

Bezos had called a meeting because he was thinking hard about the difficulties faced in the checkout process on his rapidly growing e-commerce site. To place an order, customers had to go through a long series of steps. There was a page to type in the name: click. A page to enter the first line of the address: click. And so many more clicks.

One of the 12 principles of the Agile [software development] Manifesto states, “Simplicity, the art of maximizing the amount of work that did not need to be done, is essential.” By this, they meant that the goal should be to create value for the customer, and if it can be done using less code and fewer resources, that’s exactly how it should be.

At the pharmaceutical company Pfizer, there is a program called “Dare to Try,” which emphasizes seven specific aspects to promote innovation. For example, “freshness” encourages employees to find ideas in new places; “play” draws on the curiosity and fun of children; and “greenhouse” protects early-stage ideas, however crude, from harsh criticism so that they can grow. Most perfectionist people tend to have difficulty with the idea of starting with something crude; they demand of themselves a high standard of perfection at all stages of the process. But the standard they seek to maintain is neither realistic nor productive.

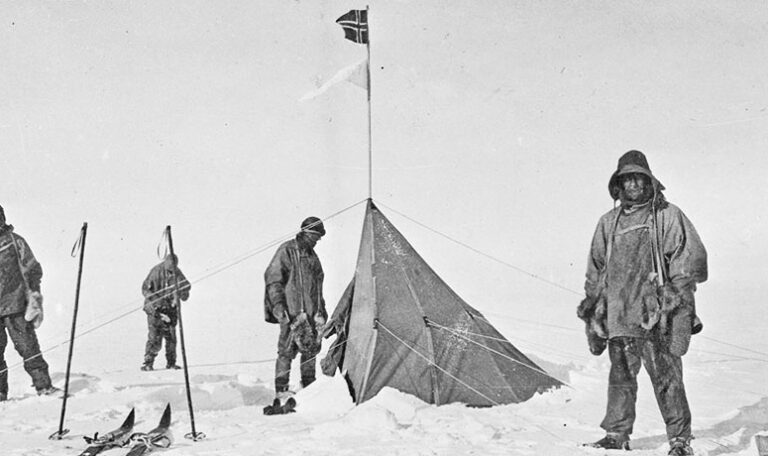

From the beginning of the journey, Amundsen insisted that the group advance exactly 15 miles a day, no more, no less. The last stretch would be no different. Rain or shine, Amundsen “would not allow the 24 kilometers per day to be exceeded. While Scott only allowed his team to rest on the days “when it froze” and forced them to an “inhuman effort” on the days “when it thawed,” Amundsen insisted on plenty of rest and anticipated a steady pace throughout the journey to the South Pole.

This one simple difference between the two expeditions explains why Amundsen’s team reached the pole and Scott’s perished. Ultimately, establishing a steady, sustainable pace is what allowed the Norwegian group to reach their destination “without exceptional effort,” as Roland Huntford, author of a fascinating book about this race to the South Pole, explains.

PART THREE – Effortless Results

Some knowledge is only useful once. For example, you memorize a fact for an exam and forget it the next day. You glance through an interesting report on your cell phone, but an hour later your brain has not retained any details.

Other knowledge is useful over and over again. When you understand why something happened or how a thing works, you can apply that knowledge over and over again. For example:

The student who learns the fundamental principles of any subject can easily apply that understanding in various ways over time.

The manager who learns how to unite his team can apply that approach to many future teams.

The person who understands how to make a decision can make good decisions forever.

If you summarize the main teachings of a book you have just read, you will absorb it more deeply. The process of summarizing, of extracting the essence of ideas, helps us turn information into understanding and understanding into unparalleled knowledge.

There is no better way to teach than through the power of stories. A good story can live for millennia. Just think of Aesop’s fables.

Aesop was a slave storyteller who lived more than 2,500 years ago in ancient Greece. To share his lessons, he told memorable stories. They were so easy to remember and pass on that they were passed on by word of mouth for generations.

The vast body of knowledge that humanity has acquired in so many disciplines has fueled extraordinary scientific, technological, and humanistic progress. But, as Atul Gawande explains, this progress has a downside. The sheer volume and dizzying complexity of human knowledge have exceeded the ability of experts to manage so much information. And this is exactly why tragic accidents, such as the Boeing Model 299 and others, happen.

Gawande, the author of Checklist, argues that we need a modest but wonderful tool: the checklist.

After Boeing test pilots implemented checklists and flew many, many times without incident, Gawande writes, the Army Air Corps ordered thousands of planes. Renamed the B-17, the Model 299 dropped more bombs than all other American planes in World War II and helped turn the game in favor of the Allies.

The beauty of the checklist is that the reasoning was done in advance. It was taken out of the equation. Or rather, it was built into the equation. So instead of getting those essential things right once in a while, we get them right every time.

There is an easier way to accomplish tasks in a team. When you have confidence in your relationships, they require less effort to manage and maintain. You can quickly distribute work among team members. People can openly and honestly talk about problems that arise and share valuable information instead of keeping it to themselves. No one is afraid or embarrassed to ask questions when they don’t understand something.

The speed and quality of decisions increase.

When you hire someone, you need to be sure that they are an honest and decent person, who will keep the standard high when no one is looking, who will deliver what they promise and do it right. If the professional is trustworthy, there is no need to micromanage, you know that he understands the team’s goals and that he cares as much as you do about the quality of the essential work to be done.

Warren Buffett uses three criteria to determine who is trustworthy to be hired or to sit at the negotiating table with him. He looks for people with integrity, intelligence, and initiative, although he adds that without the first, the other two can backfire.

It is the so-called “Rule of Three Is”.

However, if we look at the equation over a longer-term, the calculation changes. When we add up the cumulative cost of time and irritation today, tomorrow, and a hundred days later, it suddenly makes sense to invest in solving the problem once and for all. In this sense, fixing the drawer would represent a huge saving: two minutes of effort to prevent hundreds of future irritations. An impressive gain of time.

This is what I call the long tail of time management. When we invest our time in long-tail actions, we continue to reap the benefits for a long time.

But what we usually fail to recognize is that some tasks that at the moment seem “not worth it” can save us 100 times the time and irritation in the long run.

To break this habit, ask yourself:

Do you have a problem that irritates me repeatedly?

What is the total cost of managing it over several years?

What is the next step I can take immediately to move toward a solution?

Several years ago, Australian hospitals created a system to take advantage of this window of opportunity and identify potential cardiac arrests before they happen. Rapid response teams (ERR) were created, which included an emergency nurse, a respiratory therapist, and a doctor. In all units, a list of the triggers that could signal a cardiac arrest was distributed, with thresholds for action. For example, the nurse should call the ERR when the patient’s heart rate falls below 40 beats per minute or rises above 130 per minute, even if the signs appear normal.

This system was soon adopted by hospitals in the United States and resulted in a 71% reduction in code blues and an 18% reduction in deaths. One physician explained why ERRs have proven successful: “The key to the process is time. The earlier you identify a problem, the more likely you are to avoid a dangerous situation.”

Just as you can find small actions that will make your life easier in the future, you can look for small actions that will prevent your life from getting more complicated. This principle applies to every kind of endeavor.

Reminder

If you extract a single lesson from this book, I hope it is this: life need not be as hard and complicated as we make it. Each of us, as Robert Frost wrote, has “promises to keep and miles to go before we sleep.” No matter what challenges, obstacles, or difficulties we face, we can always seek the simpler and easier path.

Review: Rogerio H. Jönck

Photos: reproduction and Philipp Cordts on Unsplash

FACTSHEET:

Title: Effortless

Author: Greg McKeown

![[Experience Club] US [Experience Club] US](https://experienceclubus.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/laksdh.png)

![[Experience Club] US [Experience Club] US](https://experienceclubus.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/logos_EXP_US-3.png)