Central ideas

* Changing GDP as a goal for economic growth: the 21st-century will have a much more ambitious and global economic goal than mere growth. Economists must now think of models that meet the needs of all individuals on the planet, increasing their quality of life without putting extreme stress on the planet’s natural resources.

* The world economy must be integrated with the various systems of which it is a part, recognizing that governments, the domestic economy, NGOs, local leaders, academics, and other institutions are interdependent and contribute circularly to each other’s prosperity.

* The end of development for development’s sake: the idea that inequalities and environmental degradation are an expected and necessary side effect of wealth being generated and then distributed is a mistake. Individuals need to be empowered to be able to contribute to the generation of this wealth without prejudice to their basic needs, so as not to intensify bottlenecks that break the gross gains from economic growth.

About the author

Kate Raworth is a professor and researcher at the universities of Oxford and Cambridge. An economics graduate, she is world-renowned for her concept of “doughnut economics,” an economic model that seeks to balance essential human needs while respecting the planet’s natural limits.

Who wants to be an economist?

One definition of economic sustainability could be “promoting profit while ensuring the resources necessary, also, for the well-being of the current population and the next generations. This is quite a challenge facing humanity in the 21st century and one to which it will inevitably have to provide convincing answers.

That said, we have before us economic theories as to the main tools for leaders and opinion-makers to change laws and propose new public policies that address the main global issues that are outlined for the coming years, some of them already summarized within the UN Sustainable Development Goals for 2030, such as promoting the eradication of poverty, quality education, expanding the supply of basic sanitation and drinking water, reducing inequalities, responsible consumption and production, and decent work combined with economic growth.

1- The question is: Are the economic theories learned in universities up to this challenge?

This is the big question posed by Kate Raworth, who proposes a revolution in our economic system so that it meets the needs of people within the planet’s capacity to generate these resources. And to do this, the author argues that we must develop new theories that address the real economic problems we face, proposing “the laws that need to be proposed, creating legislation and practices as if we truly believe we are going to do this instead of talking endlessly about why we won’t be able to do it.

In general, the global economy should redefine the laws that govern it. To illustrate her thought, the author uses the financial system as an example: it should relate in the right way to the one set of laws that we cannot change: the dynamics of the Earth system.

We don’t control the climate – we can change it, but we don’t control this change – we don’t control the water cycle, the carbon cycle, or the oxygen cycle. These are data acquired from our planet. In this sense, we would need to redefine all our institutions so that they maintain the right relationship with the cycles of the living world and so that they are designed in a distributive way.

2- Changing the Goal: From GDP to Donut

Early on, Raworth uses the story of an idealistic Chinese student who ended up at Oxford’s economics faculty seeking the knowledge needed to combat the social inequality and environmental degradation plaguing the planet.

But as she begins her studies, she becomes frustrated, as she realizes that most of the content of the classes has little to do with reality, with a series of outdated thoughts and theories from previous decades dedicated basically to the study of the past without any parallel to prospects.

The drama of this student is the same as that of the author when she entered university in her country, starting her career in the prestigious non-governmental organization Oxfam, which is dedicated to fighting inequality and social injustice, passing through a brief career in the North American financial market and an African farming community.

Unhappy with her own inability to find the right tools to respond to the real dilemmas presented at the end of the 20th and beginning of the 21st centuries, she devoted herself to researching models that propose a new approach to the subject.

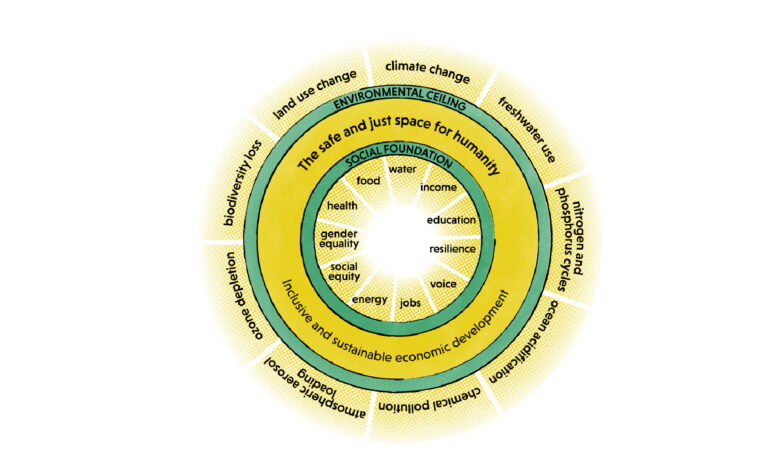

This is how the “donut” model emerged: a diagram with two concentric circles that respectively symbolize the social floor, below which is the zone of poverty and human underdevelopment, and the ecological ceiling, above which reside the phenomena of environmental depletion, such as climate change, deforestation, floods, air pollution, and overexploitation of the land.

Between these two dimensions lies the safe and just space for humanity, where development and sustainability live together in harmony.

3- Analyzing the big picture: from autonomous market to integrated economy

Next, Raworth describes the beginnings of neoliberalism, its genesis in the late 1940s, and the sedimentation of its concepts with the coming to power of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan in the United Kingdom and the United States respectively in the 1980s.

The philosopher exposes how the free market discourse and the promotion of the minimal State have guided economic thought throughout the 20th century and continue to permeate the guidelines that conduct the development of societies. For her, this progressive model without brakes has helped push several societies towards social and ecological collapse, especially those in developing countries.

Therefore, the author proposes that these dynamics should be reviewed, taking into account the insertion of neoliberal economics in a broader context, taking into account all the complex systems in which it is inserted.

For her, economists should think collaboratively, drawing on the creativity of the commons (such as Wikipedia), valuing aspects of the domestic economy in promoting prosperity at the local level, and recognizing the importance of a ‘partner state’, knowing that all these have an interdependent relationship with each other and with the living world – the biosphere, so to speak.

4- Stimulating human nature: from rational economic man to adaptable social human beings.

The 20th century had its intellectual genesis from positivist paradigms of rationality and progress. The idea of the self-made man, of the person who builds his trajectory in an isolated manner, is based on a pretended security of a state of collective “well-being”.

For Raworth, however, this is nothing more than “a painful portrait of humanity: alone, without money in her pocket, a calculator in her mind, the ego in her hands, and nature at her feet.

The author also tells us that when we are confronted with this image and recognize ourselves in it, we become even more individualistic. However, she argues that human beings have capabilities that allow them to go far beyond this: we value reciprocity, interdependence, and closeness to people, and we can integrate ourselves into the systems around us in a harmonious way.

That said, it would be time, therefore, for economic theory to take into consideration this need for integration and start proposing alternatives for these attributes to develop and function in the sense of generating prosperity and well-being for people.

5- Understanding the functioning of systems: from mechanical equilibrium to dynamic complexity

In this chapter, the author states, figuratively, that economics has long suffered from chronic physics envy. And why is that? According to her, in the 19th century, economists, amazed by Isaac Newton’s insights regarding the laws he coined to describe motion, were tempted to try to discover similar laws in economics. This, according to Raworth, does not exist.

If this were true, for example, what about economists who, relying on the equilibrium theory of markets, we’re unable to predict the storm that gripped the stock markets in 2008, when stock exchanges broke into chains and traditional investment banks – such as Lehman Brothers – went bankrupt?

The economics of this century should simply give up ready-made models and accept that complexity is part of the nature of economics. By accepting those economics, as the human science that it is, is dynamic, it is possible to gain new insights to understand scenarios such as those that led to the rise of the 1% of the world’s population that owns most of the world’s wealth and the domino effect suffered by the markets in the last decade.

In Raworth’s words, “it is time to stop looking for deceptive levers of control (which simply do not exist) and start managing the economy as a constantly evolving instrument.

6- Projecting to Distribute: from “rebalancing through growth” to a distributive conception

Here, the author discusses inequalities. In a logic that, in Brazil, has been eternalized in the popular imagination in the figure of the former Finance Minister Delfim Netto, things have to get worse before they get better, or “the cake has to grow before it can be distributed (although the former congressman insists that he never said this phrase).

In neoliberal logic, the predictable side effect of economic austerity would be an increase in social inequality, but at the end of the cycle, it would generate wealth not only to offset this drawback but also to promote social welfare.

Raworth, however, considers this logic a mistake, a failure of a model that depletes people and natural resources for the sake of growth that ultimately results in prosperity for no one.

The 21st-century economy would therefore need to recognize that markets should act as “value distributors,” going from post-growth income redistribution to pre-distribution, promoting conditions for people to collaboratively generate wealth.

By empowering populations in this process, productivity increases without generating side effects such as health problems, malnutrition, insufficient access to education and welfare, which lead to economic losses that hinder the real development of societies.

7- Create to regenerate: from “growth will clean everything up again” to a regenerative conception

One of the great current debates is around environmental sustainability versus compulsive economic development, which would be irreconcilable agents of the historical process of this century and, for this reason, are destined to be in constant conflict.

Recovering the logic of the previous chapter, an economy will not generate prosperity without first eroding the environment and then taking steps to regenerate it. And again, this is a mistake, according to Raworth.

Environmental degradation is nothing more than the result of a failed economic-industrial model, where the preservation of ecosystems is nothing more than a vague and distant promise.

And since the economy would be integrated into interdependent systems, it would be necessary to adopt another model of progress, one that is not linear but circular, in line with the Earth’s natural cycles.

Being agnostic about growth: from growth-addicted to growth-agnostic

In this chapter, in apotheotic fashion, Kate Raworth summarizes her thesis by questioning the paradigm of growth for growth’s sake. The economies of the world rely extensively on GDP expansion as if it can grow uninterruptedly.

However, this is not the scenario that is verified, since a good part of the most mature economies in the world has reached an evolutionary plateau, where growth rates, in some cases, are below 1%.

This happens, according to the author, because they were designed to simply grow, regardless of whether they make their populations prosper or not. The result: bottlenecks such as hunger, environmental pollution, logistical problems, global warming, and low quality of life that generate economic losses that neutralize the gross profit derived from growth.

Thus, the philosopher proposes a new way of thinking, where people would be “agnostic” (not to say skeptical) about growth.

For her, the logic should be reversed: economists should think of models that generate prosperity regardless of whether there is GDP growth or not. In other words, growth for growth’s sake is not sustainable, because it gives rise to side effects that make the surpluses produced useless, leading to crises and contradictions.

Review: Rogério H. Jönck

Images: Reproduction and Unsplash

FACTSHEET

FACTSHEET

Title: Economics Donut – Seven ways to think like a 21st-century economist

Author: Kate Raworth

First Edition: 2019

![[Experience Club] US [Experience Club] US](https://experienceclubus.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/laksdh.png)

![[Experience Club] US [Experience Club] US](https://experienceclubus.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/logos_EXP_US-3.png)